Deep learning for reconciliation

By Dr Rebecca Barlow, History and Global Studies Teacher

Radford College is currently formalising its commitments to reconciliation in its first ever Reconciliation Action Plan. Did you know that these efforts are operationalised through the curriculum in our classrooms on a regular basis?

The classroom is a critical site for reconciliation. Moreover, the significance of a strong education in the Social Sciences and Humanities cannot be overstated: there is wealth of research showing that students who are engaged in social justice education not only build their capacities as agents of change but also achieve better learning outcomes and report higher well-being indicators.

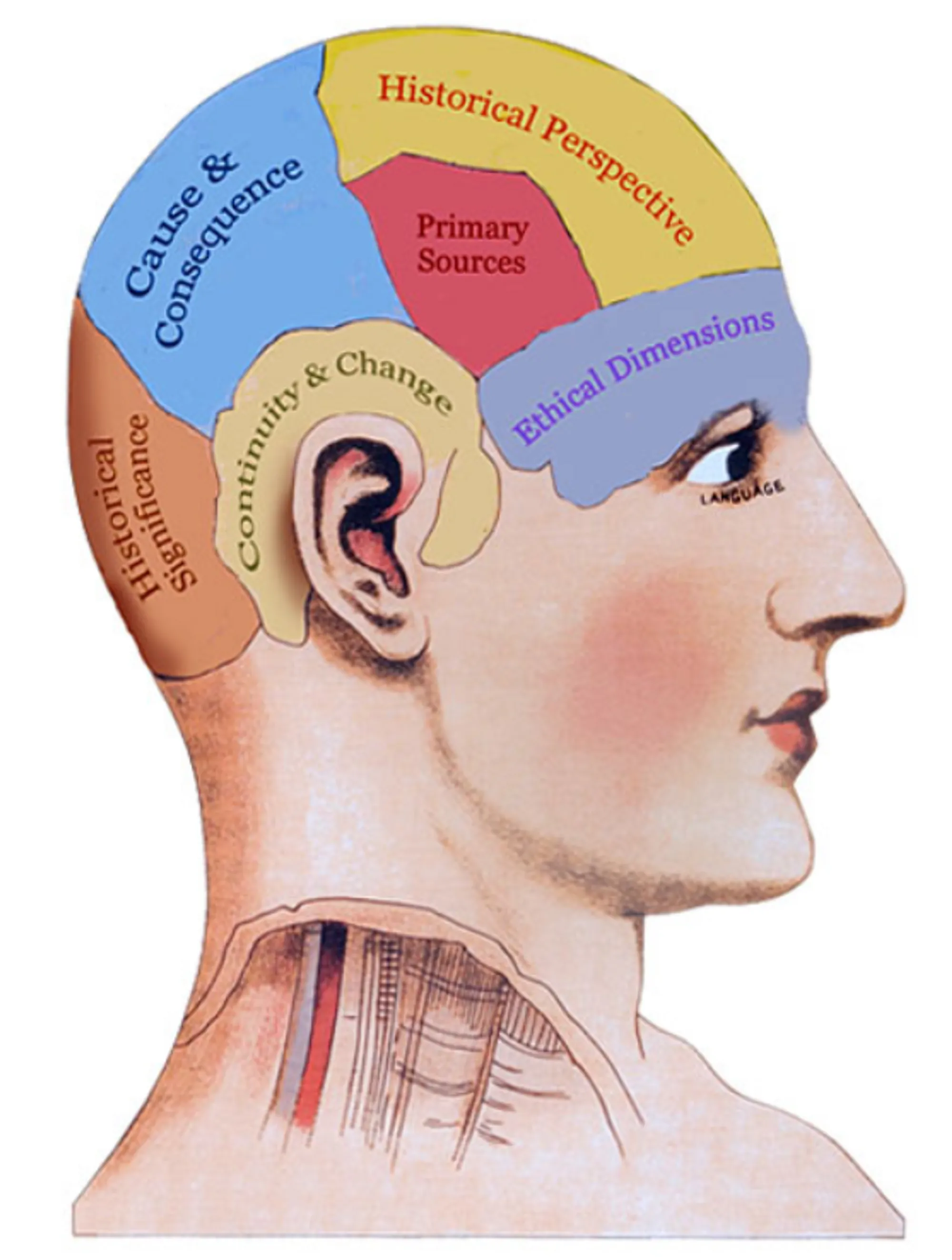

Year 10 History students spent last term delving into a study of Aboriginal rights and freedoms throughout the twentieth century to the present day. Using a Deep Learning framework to “split-screen” competencies and content, students explored themes of resistance and resilience through a range of case studies whilst engaging in regular formal reflections to consider the ethical dimensions of historical inquiry. These case studies included Eddie Koiki Mabo and Native Title, Faith Bandler and the 1967 Referendum, and Pat Dodson and the Uluru Statement from the Heart. The unit was underpinned by the philosophy of New History, which argues that the past is not neutral, and should not be treated as such in historical analysis; that ‘if the story is meaningful, we should expect to learn something from the past that helps us to face the ethical issues of today.’

Taking up this challenge, students employed the ‘I used to think … now I think …’ thinking routine from Harvard University’s Project Zero to produce “GRASPS” tasks in the form of evidence-informed opinion pieces. GRASPS – which stands for goal, role, audience, situation, product, and success criteria – is a framework for authentic assessment design which empowers learners to demonstrate conceptual understanding, critical knowledge, and higher-order skills acquired through a unit of learning. This allowed students to position themselves as experts and showcase their “lightbulb moments” in their study of Aboriginal rights and freedoms with regards to land rights, civil and political rights, and reconciliation.

Keep your eye out for updates on Radford’s first Reconciliation Action Plan, including its operationalisation in our classrooms.