T.B. Millar and Radford College

By Mrs Annette Carter, College Historian

Everyone has been inside T.B. Millar Hall, whether it be for the Radford College Art Show, a music, dance, or drama performance, but how many of you know about the man it was named after?

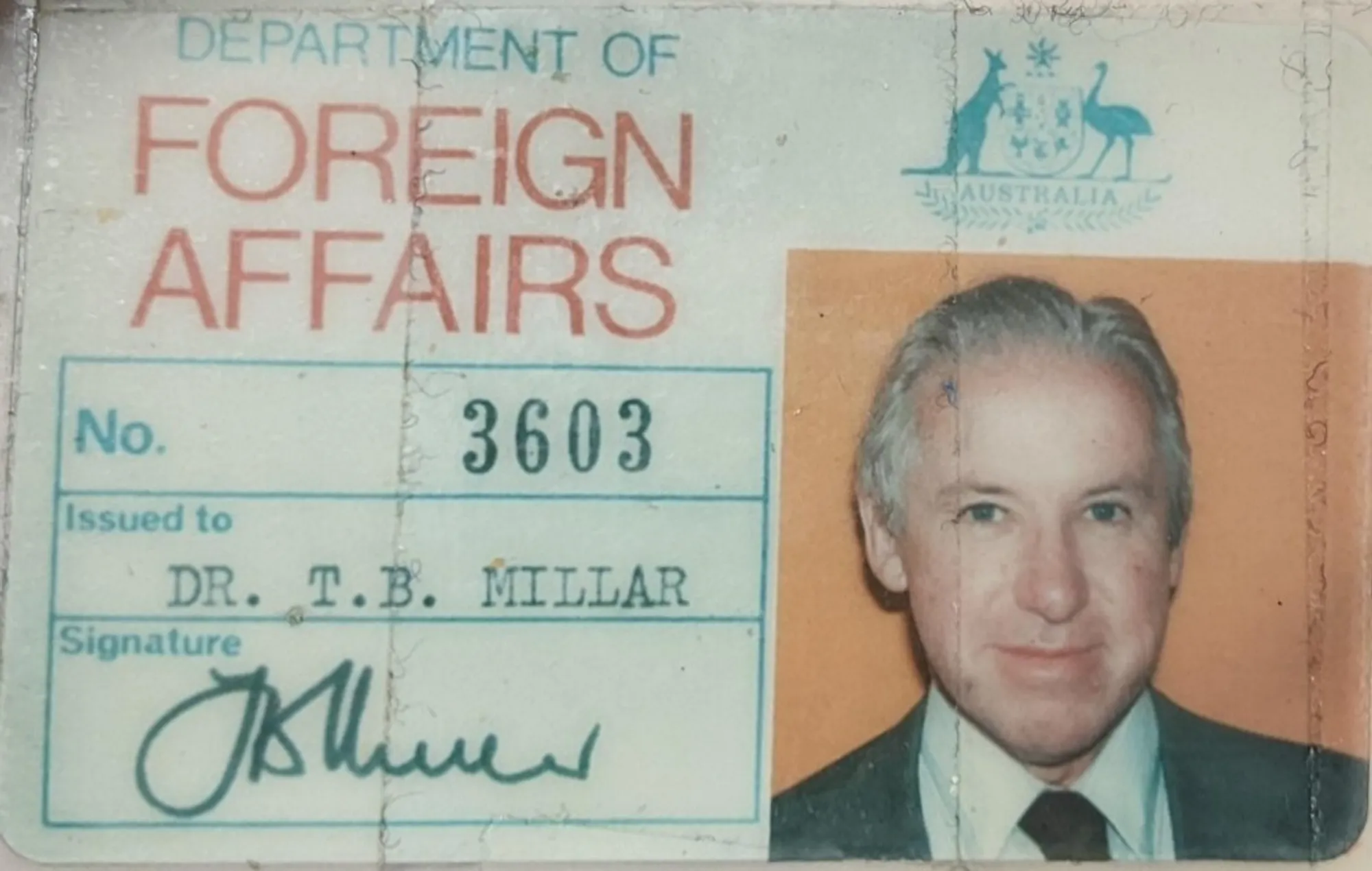

Before becoming involved at the proposed new Grammar School (that was to become Radford College), Thomas Bruce Millar had served as an officer in the Defence Forces. After WWII, he was heavily involved in academia in Australia, America and England. He did a secondment with the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, was a prolific scholar and, among many other accolades, established ANU’s Strategic and Defence Studies Centre.

In the 1970s, Millar became involved with Canberra schools. When Narrabundah College was threatened with closure, he chaired a school committee (his son Jonathan attended the school) to introduce the International Baccalaureate. It was its first introduction at an Australian school. As Chairman, he negotiated with the ACT Schools Authority, Federal Government, and International Baccalaureate Organisation. “We felt, correctly, that the IB would appeal to those many Canberra people – diplomats, defence personnel, public servants – who were inclined to move about internationally”[1] and could provide an international accreditation that enabled students to move easily between countries. The introduction of the IB at Narrabundah College was “a steady if undramatic success slowly emulated elsewhere”[2].

It was during this time that Millar received mail about the establishment of a new school, separate from the two grammar schools. He replied affirmatively supporting the decision, but did not attend the initial meetings. Millar was then invited to the new committee and, after attending two or three meetings, was invited to chair it. He was reluctant because he was heavily committed with his work and the IB implementation at Narrabundah College. He also felt that although he was an academic, he was not an educationalist. In addition, he was not a practising Anglican. Upon consultation with the Anglican Bishop of Canberra, he was asked whether he would still consider doing it.

“So began one of the most challenging and constructive episodes of my life. We had no funds, no buildings, no land, only the enthusiasm of a small group and an uncertain, unproven scattering of public support”[3].

Bishop Warren was not “wildly enthusiastic” about backing the new venture, given that he himself had attended a state school, but did give his support after attending a public meeting and having Millar speak at a Bishop-in-Council meeting.

The committee decided that the school would be:

- Co-educational

- Based on order of applying for admissions

- Pursuing excellence, developing “each girl or boy to the highest level of which they were capable”

- Involved in the community, with a tradition of community service.

Millar and the committee weathered much opposition but had a strong and wide support group in the community. Millar’s contribution at Radford College meant that he was asked to resign as chairman of the Narrabundah College IB Committee due to concerns of a conflict of interest.

Millar was outwardly involved in discussions about the school, appearing at public forums and on talk-back radio. He spoke with prominent politicians, both local and federal, and this, in turn, helped when the construction site was picketed by the Trades and Labour Council and Australian Teachers’ Federation.

Millar served as Chairman of the Radford College Board until 1985 when he accepted an appointment as Chair of Australian Studies at the University of London. Looking back, he was proud that Radford College “went from strength-to-strength” and became one of “Australia’s outstanding educational institutions”[4].

References:

[1] Thomas Millar, (undated), [Autobiography]. Papers of Thomas Bruce Millar. National Library of Australia. MS 8605. Series 12.

[2] Ibid

[3] Ibid

[4] Ibid